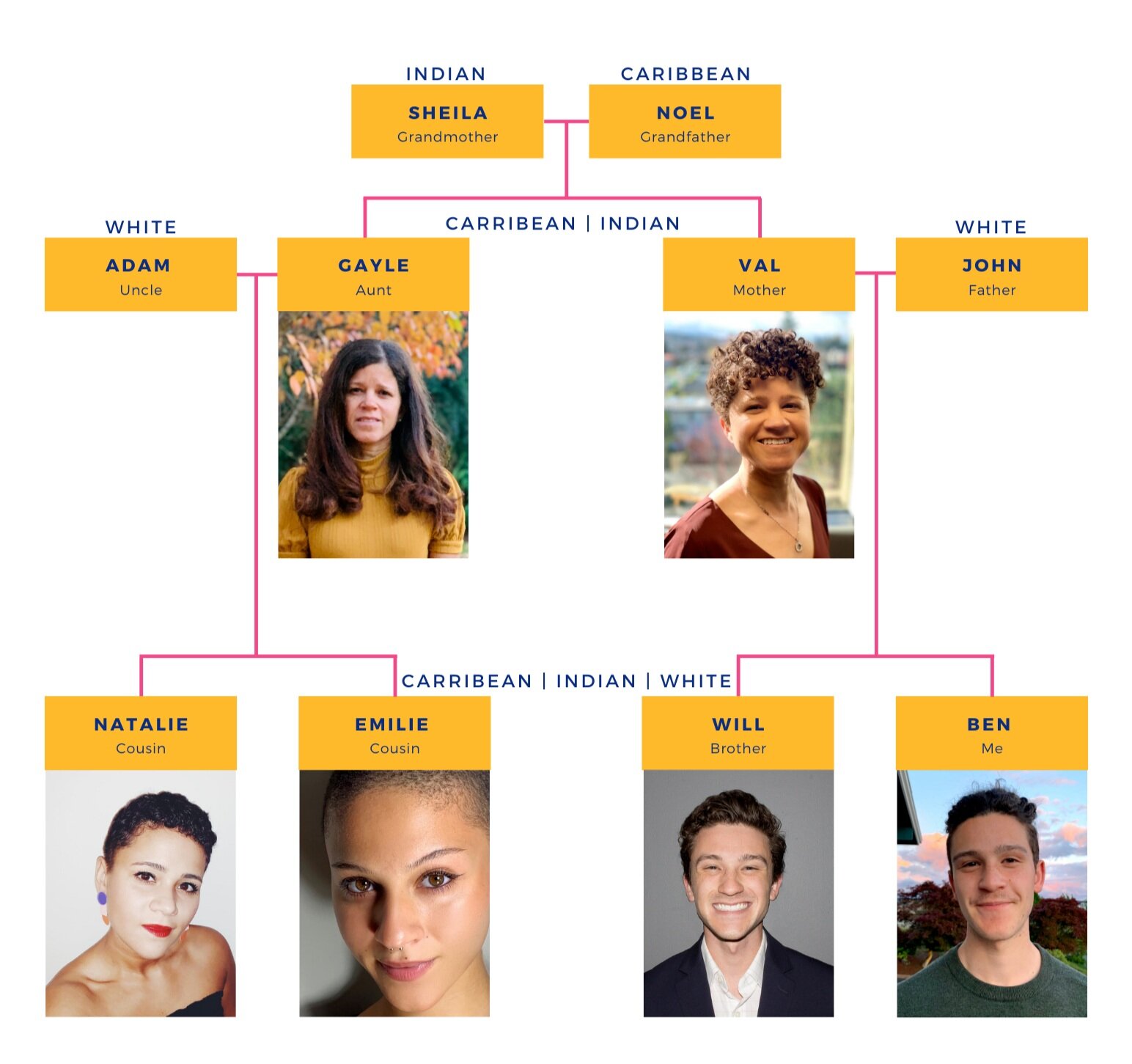

Exploration of a Mixed Family by Ben Sherman

Welcome to My Family

Growing up, we never talked about race. Despite the mixedness that ran through our veins, it was our proximity to whiteness that seemed to mold us the most. It began when my mom and her identical twin were adopted by their Indian aunt and her White husband at a young age. My mom and aunt have also spent much of their adult lives with chosen parents—a White couple who evolved quickly from distant family to mom and dad. This left my brother, cousins, and I surrounded by three sets of white grandparents and just one Indian grandmother. While I am extremely thankful for the loving family that I have, it is hard not to think about how my view of my racial identity would have been different had I been surrounded equally by nonwhite and white relatives.

As I have finally begun to explore my mixed-race identity in the last couple of years I have searched near and far to find the answers to all of the unanswerable questions. It seems foolish in retrospect, but it never occurred to me to ask those closest to me about their mixed-race experience. So, nearly two years after I first began exploring my mixedness I asked my family some questions. What I discovered was that in this struggle that felt uniquely mine, were five other people who had been tackling the same things. Mixed-raced, multiracial, and white-passing stories need to be told. My hope is for these stories to find the eyes of a mixed-raced reader searching for clarity and community. What you will find is that even within a single family, the mixed-race experience varies greatly. There is no single archetype, but that diversity is what unites us.

What is the Hardest Part of Being Multiracial?

For this section I have transcribed responses with the addition of grammatical edits.

Natalie

Not fitting in to any racial community neatly. Feeling not BLANK enough to be a part of one group or the other. Trying to navigate mixed race as an actor. I have played roles that weren't my race because I thought that was what I needed to do to "make it" and because that's what people saw me as. It has been tricky to decide when it's okay and when it's not okay to play outside of my race in theatre. So, I have been trying to actively address and confront those ideas.

Emilie

The hardest part about being mixed race is being confident in declaring my mixed-race identity. Obviously, colorism is a real and necessary thing that lighter skinned mixed race people everywhere need to acknowledge! I think what’s so difficult (and I think this goes beyond mixed race identity) is the conditioning of wanting to look white or thinking white is the beauty standard. I spent a lot of my adolescence trying to whiten myself into being “likeable” and “desirable” for the predominately white population that surrounded me. Now that I am older, I am now unlearning this conditioning to find that I am not just white but a mix of many ethnicities. Race itself is a construct that feeds whiteness, so I guess I am finding myself acknowledging my privilege racially (being more white passing), but also acknowledging that I am ethnically diverse. No one can take away my mixed heritage. I will not apologize for how I express my connection to my lineage and identity. It’s really all about continuing to listen to and aid the most marginalized.

Will

Being multiracial in and of itself isn't hard... what's hard is being multiracial and white-passing. People rarely believe me when I tell them I'm half white, so when I mark Asian and Black on demographic paperwork there's an accompanying sense of guilt. This was somewhat bothersome when I filled out paperwork for the SAT/ACT and for college, but it was a larger issue when applying to medical school. On the AMCAS application I marked White, Asian (Indian), and Black (Afro-Caribbean). Since I am white-passing and Indian and black cultures have not really shaped me, I felt like I should not claim them as part of my identity. Then there's the issue of the effect they would have on the strength of my application... with my stats I would be a slightly below average White applicant, a very strong Black applicant, and a very weak Asian applicant.

Additionally, many schools require a headshot with the application. Since I am white-passing, I feared the schools would see that I marked Black (in addition to White and Asian) and then look at my headshot and assume that I was falsely identifying myself to "strengthen" my application.

Finally, now that I have gotten into medical school, there's a sense of doubt. How large of a role did marking "Black" help me? Would I have gotten in if I had only marked White? I will likely never know the answers to these questions, but they'll haunt me for some time. So long story short, the hardest part is balancing the fact that I am multiracial (nothing can change that) with the fact that my Asian and Black heritage have not really shaped my experience.

Val

I would not say that it has been hard, but I do feel like I don't belong with any one race or group. I think my experience has been further complicated by being adopted and having my adopted father be very White.

Gayle

For me the hardest part is that others do not see me as one of them and trying to belong a certain racial group is difficult. For example, people never believe that I am from India and when I approach people from India because I identify as being part Indian, they often seem to be skeptical that I am from India. Additionally, although I am part Black, I do not identify with Black people and they definitely do not see me as being Black. I learned this firsthand when I was in college and I got a scholarship to participate in a pre-graduate program at Emory University. It was a program for Black students who were planning on going to graduate school. I applied because my advisor recommended it to me, so he obviously saw me as being part Black. However, I was never accepted by most of the students as being Black and was even asked why I was in the program. One thing I learned is that it was not just the color of my skin, as there was another female who was even more fair skinned than me and her name was Doris Day, who was fully accepted. It led me to believe that being Black is not just the color on one's skin. It seemed that the way I talked, the music I listened to, etc. made me less Black more so than the color of my skin. She even had her hair relaxed and at the time I still wore my hair natural.